Northwestern Law's Environmental Advocacy Center is supported in part by The Institute for Sustainability and Energy at Northwestern (ISEN).

As the United States moves toward a clean energy economy, how does the country ensure that economically disadvantaged communities are not left behind? A unique partnership between Northwestern Law’s Environmental Advocacy Center (EAC) and Elevate Energy, a not-for-profit organization headquartered in Chicago, are finding innovative ways to bring clean, efficient energy to all.

Elevate Energy, a 16-year-old organization that implements energy efficiency programs and renewable energy initiatives in low-income communities, has been collaborating with EAC since December 2015. The partnership combines academic rigor with applied environmental advocacy, allowing Northwestern Law students to work under faculty supervision as they help design public policy and legal strategies according to Elevate’s priorities.

“Elevate is one of our real-world clients, so the students and EAC meet with them on a regular basis,” said Debbie Chizewer, Montgomery Foundation Environmental Law Fellow at EAC. “Not only do students deliver written reports on their research, but they also present their findings to Elevate and engage in real discussion surrounding their recommendations. This partnership is about providing students with hands-on experience while also presenting a tangible good to our client.”

The Big Picture: Why focus on low-income communities?

Even policymakers who are adamant about the need to transition to a clean energy economy sometimes overlook the unique needs of low-income communities. Low-income advocates, on the other hand, are keenly aware of these needs and often call for public policies that provide extra financial support to these communities as part of the transition. There are many reasons to provide this extra support, including the following:

- Environmental justice. Pollution from the energy sector tends to disproportionately affect low-income and minority communities, and advocates stress the need to mitigate this harm as an issue of environmental justice. Common urban pollution sources include electric power plants and energy-intensive industrial plants (e.g. steel and chemical processing facilities), which tend to be located in closer proximity to low-income areas. Recognizing these disproportionate burdens, the U .S. Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed Environmental Justice Strategic Plan, 2016-2020 seeks to reduce disparities in the nation’s most overburdened communities noting that “achieving this vision will help to make our vulnerable, environmentally burdened, and economically disadvantaged communities healthier, cleaner and more sustainable places in which to live, work, play and learn.”

- Less available capital. Given constrained income, low-income households are naturally less likely to invest in renewable energy (e.g. solar panels) and energy efficiency improvements (e.g. more efficient appliances and lighting).

- Percentage of income spent on energy. Low-income households spend a much larger percentage of their income on energy than wealthier homes. According to the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE) policy research group, an average household in the United States spends 4% of income on home energy costs, while low-income families at or below 150% of the poverty line spend 17% of their annual income on energy.

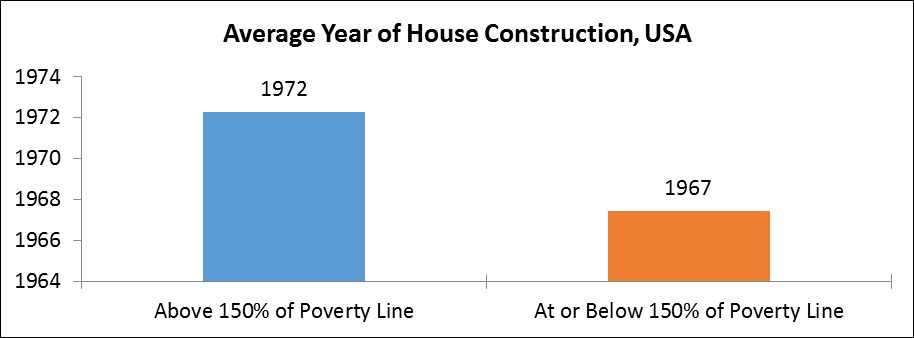

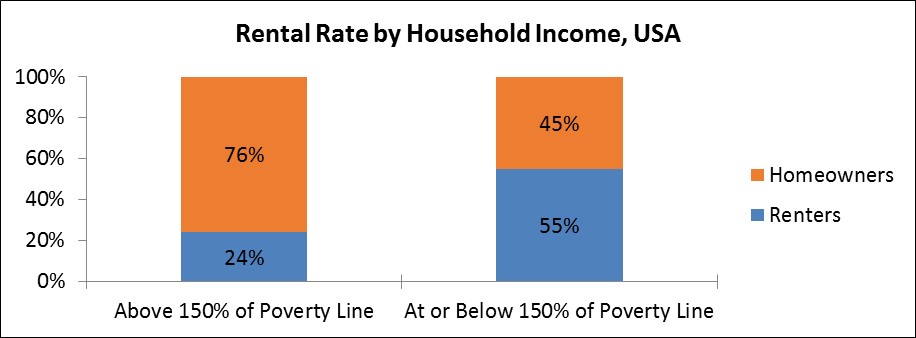

- Age and quality of housing stock. Low-income families tend to live in older homes that do not use energy as efficiently as wealthier homes (e.g. faulty electric wiring, poor insulation, inefficient appliances).

- Rental vs. homeownership. Low-income households are more likely to be renters than homeowners. As a renter with no equity in the home, households are disincentivized from investing in renewable energy and energy efficiency improvements, which typically have multi-year payback periods.

|

|

|

|

| Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2009 Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS) Microdata |

The Partnership: Northwestern’s Environmental Advocacy Center and Elevate Energy

Since the partnership began, EAC and its team of students have been helping design a policy strategy for Elevate that helps address these unique barriers faced by low-income communities. So far this year, EAC has completed two research projects meant to inform Elevate’s work—one focused on low-income state energy efficiency programs and one looking at generating funds for low-income energy programs through cap-and-trade carbon markets.

The first project, which focused on improving and expanding state energy efficiency programs, has significant implications for Illinois including reducing greenhouse gas emissions from power plants and providing cost savings on customers’ utility bills.

“Because we’re based in Chicago, we have a really good background on the low-income utility energy efficiency programs in Illinois,” said Elevate Energy’s Policy Director, Anne McKibbin. “But we wanted to have a look at what sorts of policies were working well in other states. EAC analyzed laws, regulations, and best practices in Michigan and Minnesota, which will be incredibly valuable for us.”

The cost savings from energy efficiency programs can be significant—especially for a household with constrained income. Diana Story, a low-income resident of Chicago’s West Pullman neighborhood, is expected to save approximately 26 percent annually on her gas bill thanks to Elevate’s energy efficiency programming and a forgivable loan from the City of Chicago.

“I had no idea we had places like [Elevate Energy] for people with low incomes who can’t afford to get work done,” Story said. “Now I keep my air conditioning around 76° F and rarely change the thermostat because the air conditioning seldom kicks on. I get so much joy from being able to save on my bills... Elevate Energy is really serving and helping people. I would recommend this program to everyone in my community.”

For their second project, EAC and its team of law students investigated opportunities to support low-income households in Illinois under the federal government’s Clean Power Plan. The Clean Power Plan is a fundamental component of the Obama Administration’s response to climate change and requires states to cut carbon dioxide emissions from electric power plants by one third below 2005 levels by the year 2030.

In order to inform Elevate’s public policy strategy, the team explored ways to implement state-run cap-and-trade markets as a Clean Power Plan compliance option. The EAC project complemented Elevate’s own research into the federal Clean Energy Incentive Program (CEIP), a voluntary “matching fund” program offered through the Clean Power Plan that incentivizes states to invest in renewable energy and energy efficiency in low-income communities. Ultimately, Elevate is exploring ways to combine cap-and-trade revenue with CEIP funds to bolster low-income clean energy programs.

“It makes sense that the revenue from cap-and-trade systems should be reinvested in the clean energy economy—preferably in communities that have had difficulty accessing energy efficiency and renewables in the past,” McKibbin said. “The research that EAC presented to us was a primer on carbon markets in the U.S. It will be really helpful as we think through what these policies should look like in Illinois and the region. We’ll be using this and other research as we work with partners across the energy industry to put together specific suggestions for ways in which state government can implement the CEIP in Illinois.”

EAC did not reinvent the wheel entirely. Other regions of the country have implemented funding models that may provide important lessons for Illinois.

“We studied how other states are using policies like cap-and-trade systems to generate revenue for low-income programs. We looked at best practices from places like California and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) in the Northeastern United States—both of which have well-established programs—to guide Elevate's policy recommendations for Illinois’ program,” said Chizewer.

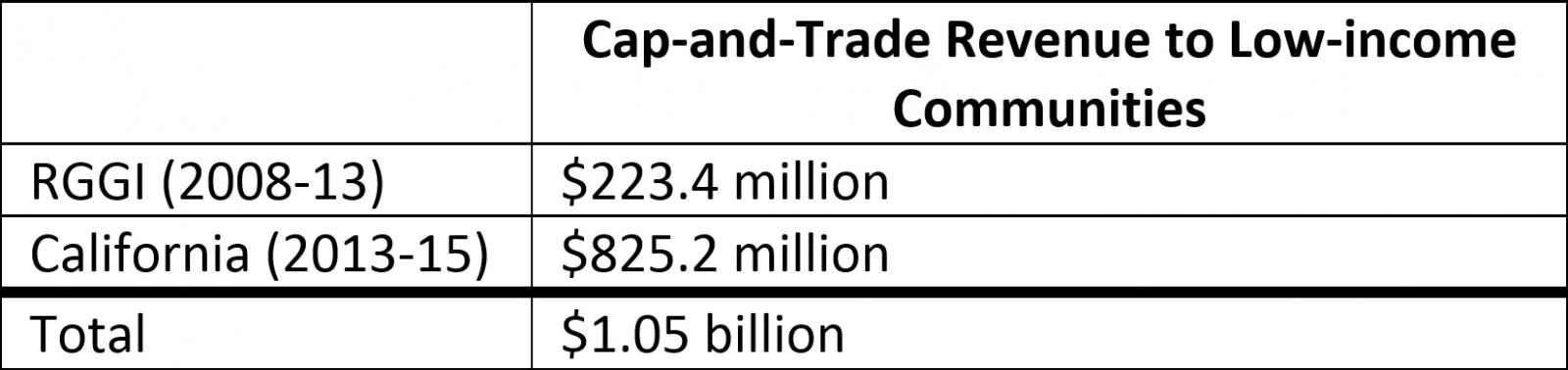

Clean energy advocates have been closely watching the impacts of these two greenhouse gas cap-and-trade initiatives, which have been in place since the early 2000s. While the initiatives differ in certain ways—most notably in the fact that RGGI spans across multiple states—they both require that a portion of revenue generated through the sale of pollution permits be used to fund energy projects in low-income communities. Since 2008, these two programs have raised over $1 billion to benefit low-income households.

|

|

| Sources: "Investment of RGGI Proceeds Through 2013" and "California Climate Investments Using Cap and Trade Auction Proceeds Annual Report (2016)" |

From Energy to Water Conservation

In the wake of successfully completed projects on energy efficiency and carbon markets, EAC and Elevate continue to explore ways to deepen their partnership. In September of this year, the two organizations sat down to explore new opportunities—this time focusing on water conservation.

“Elevate is expanding our program offerings to include water conservation assistance for affordable housing owners. Water costs are rising, and households—especially people living in affordable housing—are taking a closer look at their water usage,” said McKibbin. “We’re trying to better understand the policy landscape and funding opportunities surrounding low-income water conservation. EAC will be helping us look at federal and local laws and policies to help us build these sorts of programs.”

“Work in water conservation is an excellent fit for EAC,” said Chizewer of EAC. “It’s a question of environmental justice. Who will devote a greater portion of their income to paying for water as prices rise, and who is most likely to be impacted by leaky pipes? It’s low-income communities.”

By partnering with organizations like Elevate Energy, EAC is living its commitment to providing students with a variety of practical skills and experiences.

“Our work at EAC crosses a lot of different areas of environmental legal practice. We do litigation, but we also do a wide range of advocacy work, and we provide legal analysis in partnerships like the one with Elevate,” Chizewer said. “We recognize that not all environmental law clinic students are interested in litigation, so we provide a variety of opportunities for our students to explore their passions. At EAC, we’re committed to using our work to promote environmental and public health for all communities—whether the questions involve energy, water, climate change, hazardous waste, or air pollution.”

Photo Credit: Joel Olives