Daniel E. Horton is a climate scientist and assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Northwestern. His research interests include the detection & attribution of recent climatic change, as well as the projection of near-term climate change impacts. We spoke with him in the midst of the COP21 talks in Paris to get his take on the issues and impacts at stake.

What is your Northwestern affiliation?

I am an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

When did you join the faculty here and where were you before then?

I joined the faculty in September of this year. Prior to that, I was a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Earth System Science at Stanford University.

What are you looking forward to most about living in Chicago?

I moved to California four years ago. Those four years happened to be four of the hottest and driest on record in California. Drought, I suppose, is a type of weather, but it isn’t exactly the sort of weather that a former meteorologist gets excited about. It’s wonderful to once again be in a place where persistence isn’t always the best forecast.

Tell me a little bit about your research and how you got started studying the impacts of climate change.

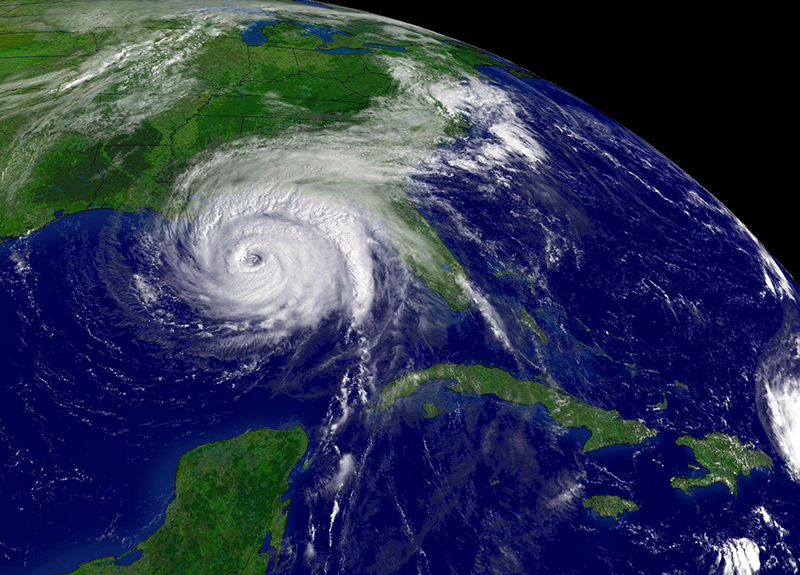

After attending Tulane University in New Orleans for undergrad, I became a weather officer in the U.S. Air Force. I was lucky enough to spend most of my time stationed in Europe, but toward the end of my service commitment, I remember standing in the weather shop at Aviano Air Base in Italy, watching Hurricane Katrina wreak havoc on the city that had recently been my home. That moment was instrumental in shaping my career transition, and shortly thereafter I returned to academia to pursue studies in climate science.

I began those efforts at the University of Michigan, where I studied paleoclimatology, a field of research that’s half climate science and half geology. After getting my PhD, I transitioned into a postdoc position at Stanford and began studying climate change impacts, or the intersection of climate science and humans.

This largely meant looking at the effects of climate change on things like air quality, infectious disease, heat waves, agriculture, and extreme weather events. In general, the goal of my research is to isolate climate influences, determine if, how, and why they may change in the future, and then assess risk for stakeholder adaptation and mitigation decisions.

What research projects will you be working on at Northwestern?

I plan to continue pursuing impacts research, but I’ve also recently begun climate change detection and attribution work related to atmospheric circulation. The terms detection and attribution refer to research that seeks to detect a robust signal of change from the noise of the climate system, and then attribute that signal to natural and/or human causes.

In the case of atmospheric circulation, I’m interested in learning if the addition of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere has changed regional circulation patterns. For example, has adding greenhouse gases changed the duration or frequency of particular circulation patterns, such as the persistent high-pressure ridge that was responsible for California’s recent drought.

In addition to impacts research and detection and attribution work, I’d also like to do a bit of paleoclimate research. The Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences is full of outstanding geologists that I look forward to collaborating with.

I noticed that your research interests are very interdisciplinary – you are interested in the societal effects of climate change on global health, for example. Are there collaborations on campus or in the area that you’re thinking about pursuing/ excited about?

I am definitely interested in collaborating with the Northwestern research community. You mention my work on public health and I’m very keen to build partnerships with Northwestern’s researchers on the health campus. Climate scientists often filter climate science ideas through a rather abstract meteorological lens. For example, a primary talking point of climate discussions concerns a 2 degree increase in global average temperatures, a number that understates the gravity of its impact. The power of interdisciplinary impacts research lies in its ability to transform abstract climate science into findings that better resonate with people.

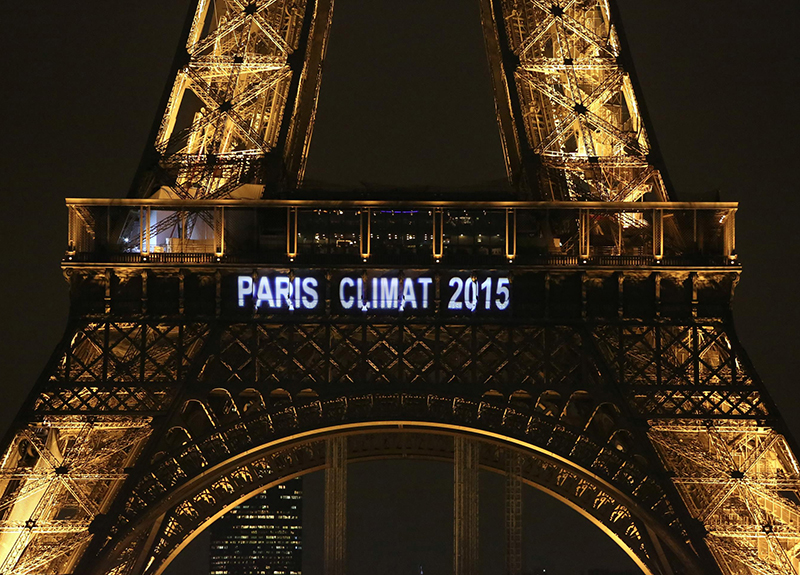

We’re in the middle of global climate negotiations in Paris. Do you think research in your field has served its purpose in informing the COP21 negotiations?

Climate scientists like to say that our research is policy-relevant, but not policy-prescriptive. In that sense I think researchers in my field, particularly through the efforts of the IPCC, have made important contributions to our understating of the physics of climate change and the impact that humans can have. That said, climate scientists are not the folks writing the accord, those are policy makers, and they must consider a host of geopolitical concerns in addition to the science.

Were there any real successes or setbacks that you’ve heard so far during the negotiations?

That depends on which news outlet you’re reading. Some make it seem like we’re going to get a pact and some make it seem less likely. I feel fairly confident that there’s going to be an agreement. One interesting story that has come out is that of the “high ambition coalition,” a sort of superblock of voting member countries that are pushing a more ambitious climate agreement than was expected. We’ll have to wait to see if they’re successful.

There’s been some debate between countries over the 2 degree warming mark, and now the 1.5 degree mark. What’s your take?

The 1.5 degree goal is great. It presents an aspirational can-do attitude that is frankly pretty refreshing in the world of climate policy negotiations. It suggests that the nations behind the movement believe in the ability of their citizens to rise up to a grand challenge and innovate for a successful future.

And last but not least, what will you be teaching while you’re here? What classes can students look forward to?

In the spring quarter, I’ll be teaching two courses: a freshman-writing seminar with a sustainability theme, and an upper level undergraduate class on earth system modeling. The writing seminar will focus on topics relevant to the Northwestern and Evanston communities, while the modeling class will introduce students to the construction, manipulation, and execution of climate model experiments, as well as the analysis of model simulation data.