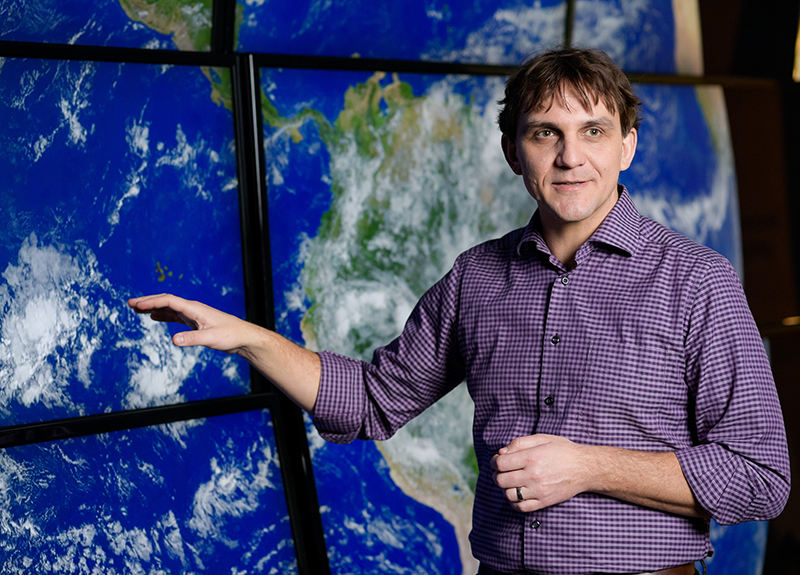

Daniel Horton is a climate scientist and the principal investigator of the Climate Change Research Group. He is also an assistant professor at Northwestern in the Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences. Article originally published by Northwestern Business Review.

Northwestern Business Review (NBR): What is the focus of your climate research?

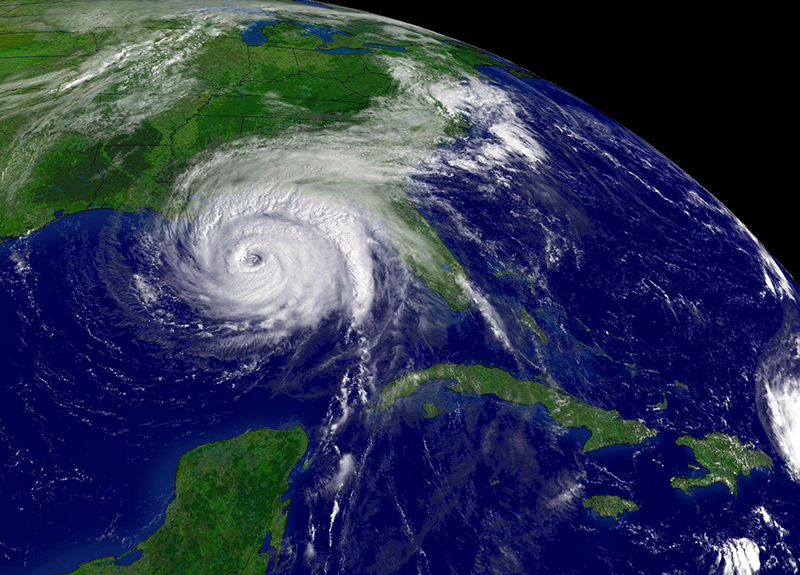

Daniel Horton (DH): So I’m interested in the intersection of climate change and humans. Broadly speaking, we call that “climate change impacts.” So I try to answer questions such as, “How will climate change influence public health? How will climate change influence the occurrence or the magnitude of extreme events?” In addition to that side of my research, I also do a bit with what’s called detection and attribution. And that is more — it’s relevant to the impact side of things, but it’s more along the lines of hard-core climate science…in terms of when an event occurs, can we say that that event was caused by climate change? Or made worse by climate change? Or, was it perhaps just caused by natural variability — the weather, chaos in a system. So those are kind of the two main planks of my research.

NBR: What is the connection between extreme weather and climate change?

DH: In the climate system, there are two things that we often talk about. There’s something called the thermodynamic side of things and then there’s the dynamic side of things. And on the thermodynamic side of things, this is something that we as scientists understand very well. This is essentially the idea that there’s more heat in the system because there’s more greenhouse gas in the system. So this results in increases in average temperature, and it also results in an increase in the amount of water vapor that the atmosphere can hold. So the impact of those sorts of things on extreme events is that with increasing temperatures, we’re going to have more heat waves. We’re going to have more record-setting temperatures, more high, high temperatures and more high, low temperatures. On the moisture side of things, when it rains, because there’s more moisture in the atmosphere, we’re going to have more deluge…more flooding events. So there’s very direct links between the thermodynamic side of things and the extreme events that we witness.

On the dynamic side of things, this is more the circulation of the atmosphere. So one way to put that would be, “Which way does the wind blow?” But more precisely, “What’s going on with the Jetstream and the large pressure systems that float around in the atmosphere?” So this is kind of your high-pressure systems and your low-pressure systems and where are they and how frequently do they occur and what’s their duration? On this side of things, on the dynamic side of things, there’s more noise in the system. So attempting to understand how climate change is influencing them is an active area of research. And so my research — I study things like heat waves, and heat waves are a combination of a high-pressure system -– so that’s the dynamic side of things — and high temperatures — which is the thermodynamic side of things. And we want to know, “Will a summer heat wave become more frequent or more intense in the future?” And so we look at both the thermodynamic and the dynamic side of that. And we want to know when it does occur, will it last longer? Because we have seen recent evidence of long-lasting heat waves, and these are incredibly destructive from a public health impact standpoint. They can result in massive casualties. In 2003, in Europe, there was a heat wave that lasted for over a week, and it resulted in 55,000 premature deaths. In 2010, in Russia, there was a heat wave that resulted in tens of thousands of premature deaths. And so these events can be incredibly powerful both from a meteorological perspective but also from a public health impact perspective.

NBR: What does the planet’s timeline look like without the implementation of aggressive climate policy?

DH: So the one thing I definitely want to stress is that climate change is not something we expect to happen in the future — it’s something that’s happening right now. We already see the effects of climate change in our daily, monthly, yearly, decadal observations. We as a society have been experiencing climate change for a long time. However, we expect those effects to get worse as time marches along. When we make projections about what the future might look like, we use climate models. And these climate models — there’s about 30 independent climate models created by national labs all over the world. And we run simulations with and without greenhouse gases. We run simulations with different versions of the evolution of greenhouse gases. These rely on projections of economists and sociologists and how they feel humanity will evolve with regard to their economy or their energy choices or human population, and things like this. And we can put all those into our climate model and look at the differing effects. And so some of those simulations use scenarios in which we implement policies that reduce the amount of CO2 that we consume as a society. And the impacts that we witness in those simulations in terms of heat waves, flooding events, things like that, are lesser than those that simulate a “business-as-usual” scenario. So I think the primary message for this question is that climate change is already happening and it’s not something that we can avoid at this point. And certainly, to mitigate the strength and frequency of many of these climate and severe weather events, aggressive decarboning of our economy is incredibly important.

One thing I definitely want to stress is that climate change is not something we expect to happen in the future — it’s something that’s happening right now.

NBR: What would you say is the biggest obstacle facing climate policy reform?

DH: Well, we’re a society — a global society built on fossil fuel consumption. And so getting something as large as the global economy to change course is challenging. There are political motivations that people have for not wanting to change, there are economic reasons, there are infrastructure reasons for not wanting to change…and getting an individual nation, let alone an entire world to shift priorities is super challenging. And that’s why an agreement like the Paris Accord is so important. It’s a global step in a different direction. And it provides at least some hope that we will start this transition aggressively and from the top down.

Editor’s note: President Donald Trump announced that the U.S. would withdraw from the Paris Agreement on June 1, two days after this interview was conducted.

NBR: I’ve heard a lot of discussion about “inconsequentialism,” or the idea that an individual can’t do anything to impact such a global problem. Is there anything we can do to combat this problem or is it going to have to come from the top down?

DH: I think to be very effective and an apt change, it’s got to come from both directions. And so there needs to be some leadership on this, there needs to be a vision from on high that provides a means to get there — but certainly, on an individual basis, our decisions matter. And the decisions we make, often in our current society, are decisions we make with — one, who we vote for and what they believe in and what kind of leadership we’re looking for. And two, we make a lot of decisions with our purchases and our lifestyle that we choose to live. And so if given the choice between a product that is kind of disposable or a product that is lasting, it behooves us to choose the lasting one. Or, there’s always the third option there, do you actually need that product at all? Can you borrow it, that kind of thing. So decreasing consumption is certainly something that could help. But again, a lot of the things that we can do to help with our climate problem are behavioral. It’s turning the lights off. It’s conserving. As opposed to just consuming, there’s the conservation side of things. A lot of the things that you can do to prevent climate change save us money. And I feel like that’s a solution that’s not as stressed as much as it should be.

NBR: How optimistic are you that this current administration will eventually recognize the danger of climate change, and what more can be done to convince climate skeptics?

DH: Well I can tell you I was recently involved in something called the American Geophysical Union Congressional Visit Day. And during this event, myself and some other earth scientists were invited down to Washington D.C. to meet with our representatives and senators. I met with people from Illinois, but there were other people there from Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi and so on and so forth. And we went into these representatives’ and senators’ offices and talked to their staffers about the importance of science funding and supporting science funding. And I can tell you that across the board, we were told that science is important and we need to fund science. No matter what side of the aisle the representatives were, that was the message they provided us. Now, the messaging that they delivered — they chose their words wisely. In some cases, people were very concerned — they didn’t necessarily want to use the words climate change, but they were interested in extreme weather events. And they understand the impacts a severe weather event will have on, say, the agricultural segment or the public health side of things. And so they are interested in that sort of research. They understand that the impacts of severe weather are large. Whether they’re willing to go so far as to say the words “climate change” is a different thing. And so I think they already understand the impacts of the sorts of things someone like myself studies, but they just might not be capable at this point of articulating them in the same language that we use due to the political realities of the world we live in right now.

NBR: What are your thoughts on geoengineering?

DH: So I have a couple thoughts on geoengineering. The first is that we as a society are currently conducting a giant geoengineering experiment — by putting a whole bunch of CO2 into the atmosphere. And the consequences of that are something that we’re dealing with now in the form of climate change. And I would say the majority of the consequences are not net positives. So from a first blush geoengineering perspective, I would say it’s a bad thing based on the current experiment we’re running. And that kind of falls into my second point, and that’s that we only have one planet, and so geoengineering solutions and experiments…we have to be certain that we completely understand them before we implement them. There is active research now in terms of what we can do from a geoengineering perspective to perhaps prepare for a “black swan” event. So we get to the point where humanity cannot bear the burden of anthropogenic, greenhouse-gas-caused climate change anymore. And we have to implement a gigantic solution, like shooting missiles into the stratosphere and putting a whole bunch of aerosols up there to reflect the sun and essentially cause solar dimming so that we’re not as warm as a society. And to me, those sort of things should be very cautiously investigated. But at this point, the challenge is so grand and the consequences so potentially dire that I do support research into these sorts of things…I don’t necessarily support implementation of these sorts of things.

NBR: What do you think are the most viable sources of renewable energy on a nationwide scale?

DH: So there was actually a really interesting article in India Times…there’s a large portion of the population in India that goes without electricity, or certainly reliable electricity. And the cost of solar at this point has come down so low that instead of building 14 new coal-fired power plants, they’ve decided to instead create that energy using solar. And so that’s a major step in the right direction. And this speaks to what’s called “leapfrog technology.” It’s kind of the same idea of what happened in portions of Africa, where people didn’t suddenly get landline telephones. Instead, they jumped right into cellular technology because they “leapfrogged” that secondary technology. And so in the case of developing parts of the world that don’t have reliable electricity, the potential exists now — as is evidenced by this example in India — that you can skip the fossil fuel step and go right to a renewable option such as solar energy.